Getting Back Into Music -- a Late Bloomer's Question

Hey y'all!

I recently got a message from a young woman in the Caribbean who is trying to get back into playing piano. It's something I hear over and over again, so I'd like to share our exchange with you! I love getting messages from my readers, so keep 'em coming!

She writes:

Hi Coty:

I came across your website by accident, and read your post about playing piano for a ballet company. I love both piano and ballet, so thought that it sounded awesome. Congrats!

I'm writing to ask some advice, as you're a professional pianist. Basically, I live in Antigua and Barbuda, in the Caribbean, and work in the field of international relations. I have natural talent in piano, but hardly any training. I did have some sporadic lessons as a kid, now and then, but never actually learnt how to read notes. Due to events in my life (mainly being very much discouraged from pursuing anything artistic, and not having the maturity to stick to my guns, as well as not having opportunities to train), I stopped playing for years. Now, at 35, I've decided to go back to piano, and am actually teaching myself how to read sheet music. I can also now play classical songs by ear and memory (Chopin, Debussy, Mozart). I will learn how to read notes quickly, hopefully soon. Since you have extensive experience in the music field, I was just wondering, if you could give some advice as to the options for a late bloomer pianist. I don't have any aspirations to be a concert pianist, or a notable pianist etc.., but I would like to make money from piano in some way, even if it's a side hustle :) The only thing I can think of is perhaps teaching kids if I am able to really work hard to hone my theory skills (in that case, what kind of certification would you recommend? I wouldn't want to go back to University for a BA for music, but maybe a shorter certification) Sorry for the long rant, but if you have any advice about possible options for a late bloomer pianist, I'd be very grateful. I look back on things, and wish that I had pursued a more artistic path, but now, I just want to look forward, and would like to find some practical expression for my abilities, if possible. Thanks so much for listening, and keep up the good work!!! Zeina

My response:

Hi Zeina!

Thanks so much for your message, I'd be happy to share my experience with you!

First off, you've already done the hardest thing: getting started! So many people have regrets about not making music, and live their lives wondering "what if". You're doing it! You're making music. Congrats, because the first step is the biggest step to take!

Your questions are very interesting to me because you are a "late bloomer". I love all of my older students because they approach music with purpose, rather than obligation. There are certainly young students who are very disciplined, but still in the mindset of going to school, studying, and doing what they are "supposed" to do, whether that means completing math homework or practicing their scales. Adult students come to music for enrichment and passion -- don't ever forget that! While you may feel like a late bloomer in some respects, the life experience you have is unparalleled; NO ONE has lived your exact life, and no one has your voice. That is one of the most important things to remember about being an artist. This will help you when you get frustrated with yourself, feeling like you need to play "catch up". Be patient with yourself.

Having said all of that, there really is no substitute for technique. Piano, like almost everything else, requires some level of technical skill. If you wanted to become a comic book artist, you would draw in your sketch book every day. If you wanted to be a top level pastry chef, you would practice in the kitchen every day. Piano is no different! The more time you invest in your craft, the better at it you will become. This isn't anything you don't already know... but there is an important distinction I tell my adult students:

Your music will have a technical side, as well as an artistic side. The technical aspect is improved by practicing your scales, understanding music theory, mastering new pieces, etc. Those kinds of things improve the craftsmanship of your playing, the technical requirements needed to express yourself on the piano. The other side, the artistic side, is what you bring to the table. The artistic aspect is improved by finding your voice. I don't mean your singing voice necessarily, I mean how you experience the world around you. For instance, how can you understand a love song if you've never been in love? How can you understand tragedy if you don't allow yourself to feel those feelings? It may sound silly, but this is just as important, if not more important, than technical skill. It doesn't matter if you have the most beautiful calligraphy skills, if you don't have anything to say it's meaningless. It's like a $6000 camera with no film, so to speak.

There are several successful musicians and songwriters who don't even know how to read music! But nevertheless, they managed to find their voice through music. There's not a specific place in music where you "have it", it's a lifelong journey. Making music, no matter how advanced you are technically, is absolutely key. Don't feel like you aren't a musician if you aren't playing at a certain level -- there's no such thing! If you make music, you are a musician. Simple as that.

But let's get more to the point -- where do you go from here?

You mentioned that your goal is to generate some kind of income through music. I think that's a great goal! But I'll tell you right now, there is no clear path in the music industry. It can be really frustrating sometimes, and it can be a matter of luck. So instead of letting your goal hinge on something you can't control, choose something you can control. Like, maybe your goal is to perform in public once a month. What opportunities are out there? This is where the work comes in. Are there any open mic night events near you? Festivals you could play at? Hotels/spas/restaurants that hire musicians? Festivals? School events? Retirement centers looking for music entertainment? The more you look, the more you'll dig up. Start making a list and brainstorm! Invite a friend over... you'll be amazed at how many ideas you'll come up with!

Keep in mind, to be a professional musician means to be a musician by trade -- meaning, someone needs your services in some way, and you have a business of providing those services. That means, your work hinges on the demand. This is where the technique comes in. In New York City, where I live, there is a huge demand for pianists who can sight-read very well. Auditions for universities, auditions for musicals, auditions for filmed projects, lessons, workshops, you name it. In all of these situations, the pianist is expected to be a superb sight-reader. Understanding the qualifications needed for paying jobs will help you focus your efforts: how do you get better at sight-reading, for instance?

I am a ballet/modern dance accompanist. While I am expected to be able to sight-read, I am also expected to understand the nature of accompanying movement, have a wide repertoire of music to choose from, and be flexible working with a variety of teachers and play in a variety of styles. This was never something I set out to do, but happened to have the skillset for. Because I play music "by ear" very well, I am able to pick up new themes very quickly and incorporate them into my repertoire. Because I am used to playing piano for musical theater productions, I can adapt my tempos to suit the action on stage, and I can work with even the most difficult directors. While I do have a lot of technical facility, the bulk of this skillset was built through my "joyous", "messing around" practice at home, trying to play my favorite songs from the radio.

If you are already playing Chopin, Mozart, and Debussy, it sounds like you've already got a quite a lot under your belt already! It would be useful to take a few lessons since you hadn't played in quite some time, just to check in that you aren't developing any bad habits in your playing. But aside from that, go forth and be brave! Would you be able to teach a beginner student the C major scale? How would you teach them how to hold their hands? Can you teach them the difference between a major chord and a minor chord? Having a certification does not guarantee you to have a full studio of piano students, and not having one doesn't mean you can't teach.

So to sum this all up, so much depends on you, and so much doesn't. Things that you can't control are job offers, the demand for musicians, which gigs already have a pianist, etc. And it's a numbers game -- if you post zero flyers advertising beginner piano lessons, guess how many students you'll get. But if you post 100 flyers... who knows? Again, you can't control that, but you can influence it a little.

But you can control your personal musical experience. Set up a practice schedule, and stick to it. Write music -- you learn SO MUCH about music when you write it yourself. Listen to music, all kinds of music. Classical, reggae, jazz, hip-hop, latin... it's all good information.

I'll leave you with this little bit of perspective. At the top, people expect you to be highly developed: the best sight-reader, or the best accompanist, or the best player of Chopin. Those are very specific skills. I would never hire someone who is primarily a Chopin pianist and expect her to be an incredible jazz improvisor, and vice-versa. That's like hiring a brain surgeon to deliver a baby, or an electrician to install a new sink.

But when you're beginning, the jobs are not that specified. You may get an offer for someone needing "light music" during a wedding reception, or an after school program needing a basic piano teacher. Or maybe the school choir needs an accompanist for the spring concert. These kinds of jobs are rather different, but not so extreme. Like hiring a handyman to move some boxes and then hang a few shelves, you can get more work early on by being a bit more diverse.

So be diligent on honing your skills and find target areas for improvement. When you start looking for ways to apply those skills and find a music gig, don't dwell on what you don't know -- focus on what you do know. Play out as much as you can, and meet other musicians. Be on time (early). Have everything you need. Be easy to work with. Be the solution to someone's problem. And most importantly, be yourself.

Best,

Coty Cockrell

Let me know in the comments below what you think -- do you have any ideas for Zeina? Are you also a "late bloomer" to music? If so, how do you stay motivated? I'd love to hear your perspective!

Welcome to Tel-Aviv

This is going to be a much shorter post than my usual sort because it's 1:30am here in Tel-Aviv, and I have an early morning call. This city is INCREDIBLE. The mixture of people and language and food is a little dizzying. While I haven't yet spent any time on the beautiful beaches here (the waters of the Mediterranean are as captivating as you would imagine), I plan to. Oh, I plan to. In the mean time, I've been trying to get some work done, in between my duties with the ballet company. Between applying for a super neat grant for something in the future (no spoilers yet!), recording and editing some videos for the website, and coordinating with the people at the US Embassy in Sri Lanka regarding this summer's adventures, it's been a full couple of days!

Jet lag still lingers on -- I stay up too late, and wake up too early. There just isn't enough coffee. I went to Jaffa and took some photos of this stunning little port town to the south of Tel-Aviv, but I'll tell you about that later (with photos!) Until then, just trust me... it's beautiful.

There are a lot of cats here, just running around. I don't know, maybe we have a lot of strays in New York? But it seems like they are EVERYWHERE here.

Let's see, beaches... food... lots of cats... I've covered a lot of the first impressions. Much more to come later. :)

The Theory of Musicality: Chords 201

If you’ve been keeping up with my introduction to chords and chord symbols over the past few weeks, congratulations! With a little bit of time at the piano, you should now be familiar with all these chords: Major, Minor, Major 7th, Minor 7th, Dominant 7th, Sus2, Sus4, Add2, Open 5th, and (Add)6. That’s a lot! With little more than this information, you can now open up any pop fake book and interpret most of the chords in pretty much every chart. Go you! (If you’re just now joining us, you can get totally caught up in no time by starting HERE) However, our ambitious journey doesn’t end here, we’ve only just started! This week we look at a super fun (and super easy) concept: Slash Chords.

Nope, not those kinds of Slash chords.

If you’ve been keeping up with my introduction to chords and chord symbols over the past few weeks, congratulations! With a little bit of time at the piano, you should now be familiar with all these chords: Major, Minor, Major 7th, Minor 7th, Dominant 7th, Sus2, Sus4, Add2, Open 5th, and (Add)6. That’s a lot! With little more than this information, you can now open up any pop fake book and interpret most of the chords in pretty much every chart. Go you! (If you’re just now joining us, you can get totally caught up in no time by starting HERE) However, our ambitious journey doesn’t end here, we’ve only just started! This week we look at a super fun (and super easy) concept: Slash Chords.

Before we dig into this week’s lesson, I’d like to take a minute to chat why we use chord symbols in the first place. Like we’ve touched on before, chord symbols are a musician’s form of “harmonic shorthand”; they tell the musician at a glance exactly what notes are in the harmony. But the question remains: since people already write down the notes in sheet music, why should we care about chord symbols?

tl;dr: chords are super great and helpful, but you should probably read proper sheet music too

Look at all these squiggles! Ain't nobody got time for that.

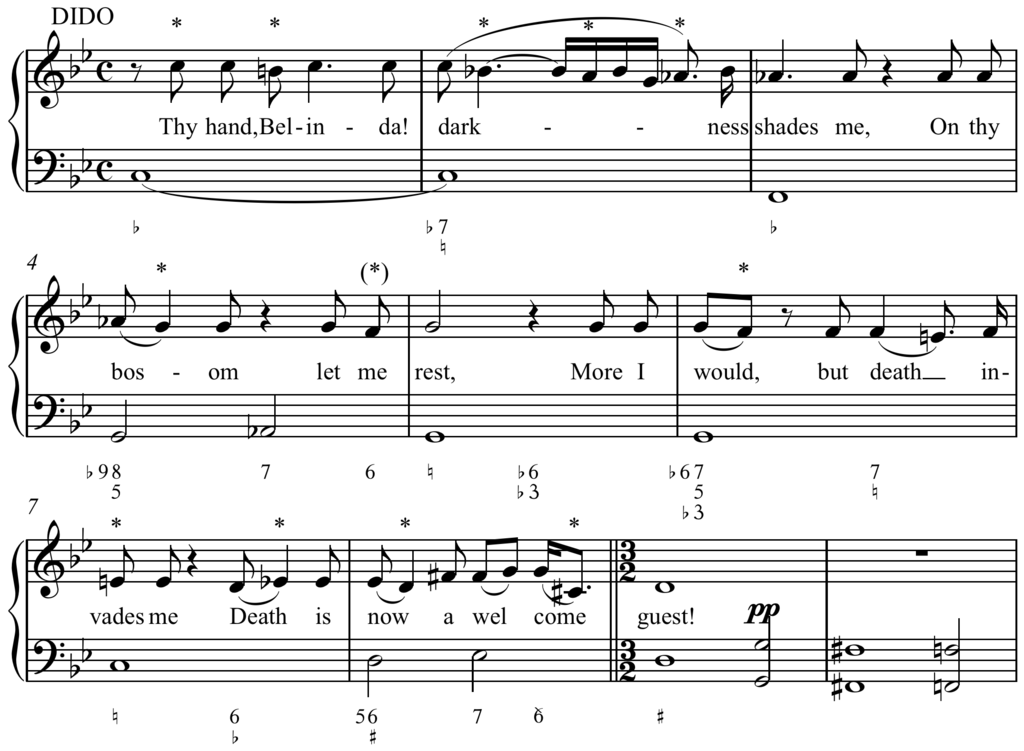

Formalized music notation used in standard music notation (all those little “squiggles climbing over a fence”) is a fantastic system for writing down exactly what notes you want played, when to play them, and how long to play them for. This system developed over hundreds of years, starting with monks and scribes elaborately penning down sacred music, and evolving into the precise system we use today. Even so, it isn’t a perfect system; while it may work particularly well for Western art music (see “classical music”), it is not the best system to capture the nuances, and even more the actual practicality of music-making for countless genres of music.

Bobby McFerrin and Yo Yo Ma

Bobby McFerrin (if you don't know who that is, google him ASAP) tells a story about his cellist friend, Yo Yo Ma. Seeking to expand his knowledge of improvisation, he travelled to a remote village in Botswana to share his music, and experience the local musical culture of the people there. In one anecdote Yo Yo Ma found himself transfixed by a song that the village shaman sang for him. He quickly got out his manuscript paper to write down the tune, and asked him to repeat the song so he could ensure that he wrote it down accurately. But when the shaman repeated his song, the melody was different! McFerrin goes on to say:

“And Yo Yo is saying But that’s not the piece you sang before. The shaman laughed and said “The first time I sang it there was a herd of antelope in the distance and a cloud was passing over the sun.” So this is the part that we lost. Every time a piece of music is played, one time there is a herd of antelope, and one time there’s not. And we turn in these cookie-cutter performances. Everything is so laid down and regimented and locked-in and so rehearsed, that they squeeze the life out of it. It no longer has any life in it because no one is open to surprise, no one is open to any spontaneous event that can happen. Everything is just dictated, and this is the way it’s gonna be. I think that’s the part that we’ve lost.”

This isn't to say that formal music notation is too fussy to be practical, but that it might not be the best solution for every kind of music. After all, there's a huge musical world outside of Western art music! (Check out the segment with Bobby McFerrin here, it's a great read!)

Standard musical notation not only struggles to give a musician freedom to improvise, but it also can be very cumbersome! This is really where I find the biggest payoff for the chord symbol system: in genres like jazz, pop, and rock where exact musical arrangements may not be necessary, the chord symbol system gives freedom to the musician to more easily interpret the harmony. In layman’s speak, you’re not wrestling over trying to read a bunch of little notes, but rather getting the gist of what the harmony is, so you can actually get the notes under your fingers and spend your time playing, not squinting at squiggles.

This isn’t to say that the chord symbol method is watering-down the music. Rather, it relies on the musician’s stylistic knowledge of the genre. This is why listening is so important! If you want to play great blues licks, listen to great blues players. If you want to sing great R&B riffs, listen to great R&B singers. And for goodness sake, if you want to play great jazz solos, listen to great jazz solos.

Standard music notation is like a very elaborate recipe from an award-winning chef: Follow these instructions exactly, use the freshest ingredients, and execute the preparation well and you will get the award-winning meal you hope for. The chord symbol system follows the same pattern, but is more of a “passed down from your grandmother” sort of recipe: all of the same rules apply, but you have more freedom to mix things up… provided that you know the basics first. You don't want to disappoint your grandmother, so you better practice rocking out with your chords.

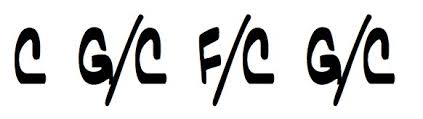

With all that said, let’s roll our sleeves up and get into today’s topic, slash chords! In the most simple sense, a slash chord is just a chord played in the right hand, with a note other than the root played in the left. That’s it. Seriously.

In all of our previous examples, we’ve been looking at how chords are constructed in the treble clef (piano, right hand). They have all been in root position, meaning that the root of the chord is the lowest note in the chord. For a C major 7, that means that we would start with the C on the bottom, followed by E, G, and B stacked right on top. But what about the left hand? Up until now, the left hand would simply play the root note in the bass clef (left hand), which is a C. Pretty easy. What bass note would the left hand play for an Fm7 chord? You got it, an F. How about an Absus7? Ab! D7(b9 #11 b13)? If you panicked a little but said D, you are correct!

However, sometimes you might not want the bass to play the root note. If the bass is always playing the root, it can sound boring and predictable. It can also be jumpy since it has to hop around all over the place! With slash chords, you can quickly and easily see what note to play in the left hand. (In a future lesson, we'll look at how slash chords can even help to simplify some really complex jazz chords into easily digestible bites! Yum!)

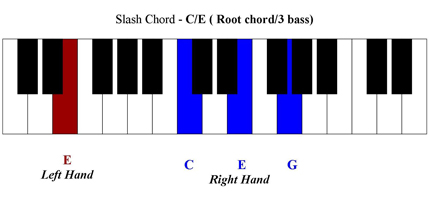

Let's look at some examples of slash chords. Below we have an example of a C/E chord. The C tells us that we are to play a C major triad in the right hand, and the part after the slash tells us to play an E in the left hand. This "C over E" chord looks like this:

When you take a chord and flip the notes up in such a way that the root is no longer the lowest note, we call that an inversion. (For more info on chord inversions, check it out here) The cool thing about slash chords is that, with the right and left hands playing together, we can get an inverted sound but still play all the right hand chords in root position. Eventually, you will find new chord voicings that you like, but when you're just starting out it is so much easier to think of chords in root position.

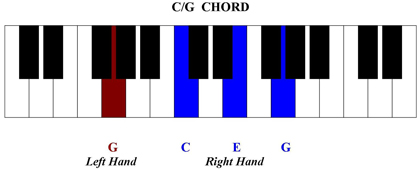

What happens if we put the next note in our chord on the bottom? What would we call it?

Why, a C/G! C major triad in the right hand, G in the left hand.

Now let's look at a chord with four notes in it:

Inversions of a C7 chord

In this example, we've taken a C7 chord and simply inverted it, each time taking the bottom note and moving it to the top.

In these three examples, we are just using the other chord tones to play in the left hand. But be creative! You can really play anything in the left hand and make it a slash chord. Depending on how the notes sound together, you may get a combo that creates tension or release. Depending on the bass note that you add, you may actually create a new chord altogether! Check out this example:

Slash chords, and the composite chords they create

Some of these combinations create some fairly advanced chords, but there are a few that we can understand at this point in time. Check out the Eb/C chord. The first thing to look at is the root in the left hand. We know that it's something over C, whether it's a C chord or not. Keep that in your back pocket for now.

Now look at the right hand. That low Bb is doubled, so we can ignore it. What's left is a perfectly stacked Eb Major triad: Eb, G, and Bb. Now, let's put those things together! C on the bottom, then Eb, G, and Bb on top. What does that sound like? A Cm7 chord! Check out some of the other chords and see if you can recognize any other similarities with chords you already know!

Now it's your turn! Find some music that has slash chords in it and go to town! Or you can get even more creative by discovering your own slash chords! Start with a triad in your right hand and the root in your left, and just try different root notes! Walk your left hand up and down, trying all the white and black notes with your triad until you get to a sound you like. What chord is that, what is it called? C/Ab, D/C... even try bigger chords like BbM7/C, EbM7/C, D7/E... have fun! Keep a notebook, writing down your favorite combos, I want to hear all about it in the comments!

Coty Cockrell is a freelance musician and artist living in Brooklyn, New York working as a jazz pianist/singer, professional ballet accompanist, theatrical music director, and vocal coach. When not teaching private lessons, he performs in the NYC area as well as internationally.

To inquire about booking or to schedule a trial piano or vocal lesson, please visit the Contact page.

The Theory of Musicality: Chords 102

In my last post, we kicked off our journey into the land of chords and chord symbols. We talked about improvisation way back in the day (see also: Baroque Era), defined just what the heck a lead sheet was, and discussed why we even care about chord symbols in the first place. Finally, we got right down to the nitty-gritty and deciphered some chord symbols as we learned the five basic foundation chords, Major, Minor, Major 7, Minor 7, and Dominant 7. I hope you practiced at home between then and now, because today we're going to make things a little more spicy!

In my last post, we kicked off our journey into the land of chords and chord symbols. We talked about improvisation way back in the day (see also: Baroque Era), defined just what the heck a lead sheet was, and discussed why we even care about chord symbols in the first place. Finally, we got right down to the nitty-gritty and deciphered some chord symbols as we learned the five basic foundation chords, Major, Minor, Major 7, Minor 7, and Dominant 7. I hope you practiced at home between then and now, because today we're going to make things a little more spicy!

When you look inside a chord dictionary (in case you haven't already), you will find a staggeringly extensive list of chords and "voicings" (meaning what order the notes are played in, top to bottom). These massively dense reference books can be unwieldy and overwhelming. The reason I bring this up now is to note that we are focusing on some of the most common chords first, then expanding our focus to the more advanced chords later. Stick around long enough and you'll learn some truly fun chords, like half-diminshed 7, or flat 9/sharp 13!

Our good ol', trusty C Major triad, in root position

Let's look at a simple major triad to start, shown above. For consistency, we'll stay in the reference key of C Major just like we did in the previous entry. In switching between major and minor, we changed the third of the chord to either a major third or a minor third. But what happens if we move that note around a bit more? Let's shift that middle note down a bit.

One halfstep and we have C Minor...

C Minor, in root position

...but what happens if we go down one more halfstep?

C2, or Csus2, in root position

This chord is called a Csus2, or sometimes simply C2 for short. The "sus" is short for "suspension", and it refers to how a note likes to resolve. In earlier music, these notes (in this case, the second scale degree) created tension, and were usually resolved by moving them up or down to the closest chord tone. In this case, that would most likely be the third of the chord, or E. In classical music, this sort of relationship would be called a "2 3 suspension". (For more info on nonharmonic tones, check out this handy study guide from the nice people over at Georgetown University)

However, in modern music a composers often prefer the slightly unresolved sound of a sus chord and might not necessarily need it to resolve. By not including a third of any kind (neither major nor minor), the chord takes on an ambiguous, transient quality. Stable because of the root and perfect fifth, but somewhat undefined. Personally, I love sus2 chords.

If you keep moving the middle note down another halfstep, you get a SUPER crunchy chord that, to my knowledge, does not have a name. We're gonna just call it some kind of "cluster chord", turn around and head back.

If you shift the middle note of a major chord up by a halfstep, we come to our next new chord, the sus4 (often just called a "sus" because of its commonality).

Csus or Csus4, in root position

The sus4 chord is super common, and the middle note loves to resolve down from the fourth scale degree to the third. Sometimes it even pops over to the second scale degree before coming back up to the third to stay (we hope). Since the "4 3 suspension" sound is so incredibly common, you will likely see this chord written both as Csus4 as well as simply Csus. The sus4 has a similarly transient sound as the sus2, but because the middle note is only a halfstep away from resolving down to a major chord, our ear tends to give this chord a bit more sense tension. Even so, it certainly isn't uncommon for composers to use this suspended sound as homebase, especially in jazz.

If you keep moving the middle note up, the chord also gets SUPER CRUNCHY just like before because of the halfstep between the middle and (this time) the top notes. You can name this chord if you like! Send me $50 and the "Jeff Chord" could be a reality.

Just by moving the middle note around in a basic triad, we can have a Sus2 chord, a Minor chord, a Major chord, or a Sus4. Neat! Now let's see what happens if we start adding notes to our major triad.

In the previous lesson, when we added notes to a triad we added the seventh. Let's look at some common additions that aren't seventh chords:

Cadd2, in root position

If you add the 2nd scale degree to a C Major Triad, you get a Cadd2 chord. You can do the same to a minor chord, although I can't say that I've often seen a C Minor Add2 chord in the wild.

If you add the 4th scale degree to a C Major Triad, you get another crunchy chord (due to the halfstep between the E and the F). In recent years, I have really grown to appreciate the tension that is produced by this kind of sound, but for our purposes this is another cluster chord.

The other major Add-type chord we're going to look at today is the C6. This chord is nice and stable, but has a little bit more pizzazz than a regular major triad... sort of like a major triad with sequins. Note: It's called a C6, not a Cadd6. It's just a regular old C major chord with the 6th added. It can also be minor, called (you guessed it) a Cm6.

Since we're only really dealing with "diatonic" notes, or notes that are within the key, the only possible notes we can add to a C Major chord are D, F, A, and B. If we add the B on the top of this major triad, we come across something we've already seen before...

...a CM7. But of course, you already knew that from the last lesson!

We've thrown in an extra note and moved things all around, but what happens if we go the other way? To quote Val in The Birdcage, "Don't add! Just subtract!" This one is super easy, but warrants a bit of explanation anyhow. If you start with a C Major chord and get rid of the third altogether, you're left with a very plain, open sounding pair of notes called a C5.

C5, in root position

In the most traditional sense, this chord hardly even qualifies as a chord. We don't know if it's major or minor because there's no third! What is left is a sort of open shell, a perfect fifth interval (sometimes called an open fifth). There is a really neat explanation to why this, and other, intervals are described as being "perfect", but we'll get to that another day. Maybe.

Alright, let's wrap things up and recap! We bounced around quite a bit in this session. Let's start with what we covered last time:

Complete chord chart from Chords:101 session

Now let's add our new chords to this list! Take extra care not to get the C2, C5, and C6 mixed up! They look similar, but one has three notes, one has four notes, and one has only two notes!

Complete chord chart from both sessions, Chords:101 and Chords:102

Woah! That's a whole lot of chords! Just like last time, use this list as a decoder ring and figure out the chords in every key... or at least a few! Some of these chord names have nomenclature that is very intuitive, but some don't! I've pointed out some of the tricky ones along the way that confused me, so please let me know in the comments if you have any further questions!

Even if it makes sense to your eyes, FIND A PIANO and get your hands on these chords! I promise you, the tactile experience will help you retain this info so much easier. Start memorizing these now and you'll have no problem at all when we get to Chords:201! That's where we're going to get into some really funky chords, including slash chords! I can't wait!

Coty Cockrell is a freelance musician and artist living in Brooklyn, New York working as a jazz pianist/singer, professional ballet accompanist, theatrical music director, and vocal coach. When not teaching private lessons, he performs in the NYC area as well as internationally.

To inquire about booking or to schedule a trial piano or vocal lesson, please visit the Contact page.

The Theory of Musicality: Chords 101

I mentioned in an earlier post that I'd dive into more detail and really break down chord symbols and how to understand them, and this is the start of that journey! Once you get the basics down for how chord symbols work, it will unlock a whole new way of thinking about music! This "harmonic shorthand" is the key to quickly playing pop songs, changing the key of a song (so that it's in YOUR range), and even writing music of your own! It may seem a little tricky at first, but we're going to break it way down.

I mentioned in an earlier post that I'd dive into more detail and really break down chord symbols and how to understand them, and this is the start of that journey! Once you get the basics down for how chord symbols work, it will unlock a whole new way of thinking about music! This "harmonic shorthand" is the key to quickly playing pop songs, changing the key of a song (so that it's in YOUR range), and even writing music of your own! It may seem a little tricky at first, but we're going to break it way down.

Before we begin I should say that I am assuming that you, brave reader, have some working knowledge of musicmaking. You don't have to be a music theory wizard (unless you have a neat wizard hat), but it will be very helpful for you to understand some basics, like which notes are which on the staff, and the difference between major and minor. There are some really great music theory resources online, such as www.musictheory.net. You can also check out the iPhone app Nota, which appears to be a great, all-inclusive app for bringing you up to speed. (If you find these resources useful, or have suggestions for other resources, please leave a link in the comments! I'd love to hear about your experience!)

Gettin' down in the "Baroque and Roll" Era

So what is a chord symbol anyway? Why are they so important? Just for a moment, let's jump back in time to the Baroque era (1600-1750). In classical music at this time, it was very common for ensemble pieces to have something called a basso continuo (meaning "continuous bass"), which was simply a form of improvised accompaniment played on an instrument capable of playing chords. Since the piano had not been invented yet, that meant either a harpsichord, organ, lute, guitar, or harp would play the accompaniment. Often, another instrument would play the lowest notes, usually a cello, double bass, or bassoon. In this way, we have an instrument (or instruments) playing the bass line, and an instrument playing the harmony notes, allowing a solo instrument to play the melody on top. This basic recipe for ensemble music (bass+accompaniment+melody) has proven through the ages to be quite a successful combination.

Although most people think of modern jazz and rock music when they think of improvisation, the truth is much of Baroque music was improvised, some 300 years before mainstream popularity of jazz in America! To save the composer time and to relegate some creative freedom to the performer, a system known as "figured bass" was developed. In this system, the melody was written in the treble clef, the bass line was written in the bass clef, and a special system of numbers was used beneath the bass notes to indicate what the harmony should be. (If you want to really put on your waders and slodge into Baroque harmony, Michael Leibson's explanation on his page Thinking Music is a pretty good one.)

You don't have to understand how figured bass works (in fact, I had no clue it even existed until college) to get the big take-away: chord symbols are harmonic shorthand, and you just need to understand the language. With figured bass, the bass line was written out, making it even easier for bass instruments to play along. With that covered, the harpsichordist or lutist simply needed to fill in the rest of the harmony as it was spelled out. With modern chord symbols (and the modern piano), usually both of those tasks will be carried out by the pianist... unless you have an awesome bass player.

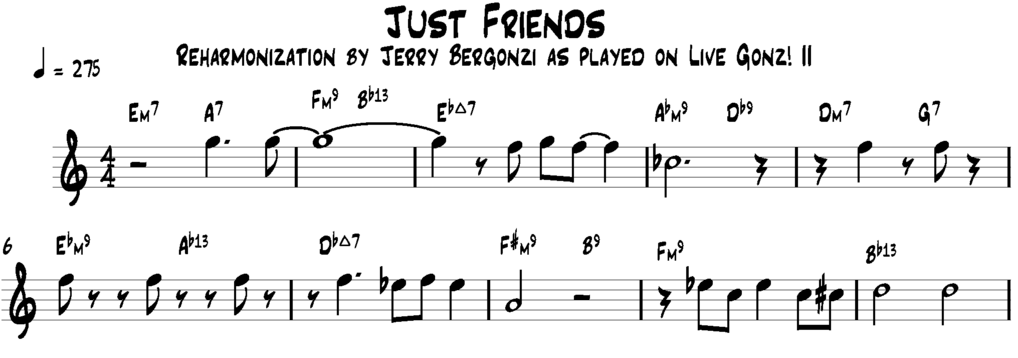

If you checked out the graphic at the top of this post, you saw an excerpt of a lead sheet called "Just Friends". A lead sheet is a shorthand version of a song; it usually contains the melody, sometimes lyrics, and chord symbols. (If you've heard about "fake books", that's what we're talking about) We're probably all familiar with melody and lyrics, so let's break down the chord symbol bit.

If you look at the example above, you'll see a mysterious little F floating above the first note. That's a chord symbol! A letter all by itself with nothing else after it tells us that it is a major chord. It's also in root position, meaning that the lowest note in the chord is an F.

The next chord symbol we see is Bb, which means we simply play a B-flat major chord underneath the melody. So far so good! Our third chord symbol is the first wacky one we've had, so let's check it out. The A means that root of the chord is A, but the next letter is a lower-case m. That means that it is minor. Since it is understood that a root all by itself is major by default, we have to add the lower-case m to indicate that it is minor. So what we have is an a minor chord... but what's with the numbers? The 7 after the m indicates that we add the minor seventh on top of this minor triad.

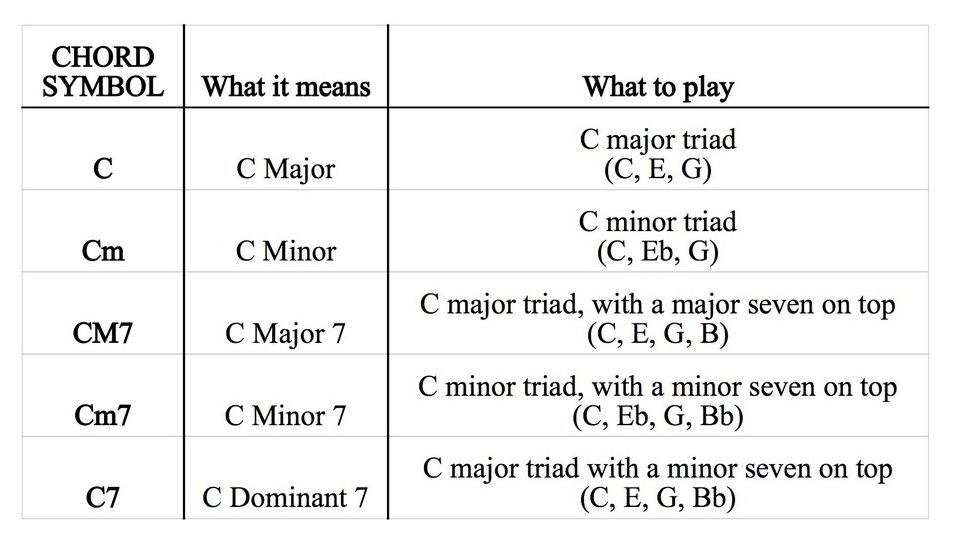

If I just lost you, don't fret: 90% of confusion with chord symbols comes from understanding 7 chords. We have a few moving parts here, so let's isolate. For the purpose of simplicity and clarity, I'll use C Major as an example.

The two factors here are whether it is a major triad or a minor triad, and whether the seventh is a major seventh or a minor seventh. Adding the appropriate 7th, a C (major chord) becomes CM7 when the major 7th is added, whereas a Cm (minor chord) becomes a Cm7 when the minor 7th is added. The only wingnut in the bunch is the dominant 7, which is just written as C7. (There's a lot of theory for why this is the norm for dominant 7th chords, but let's not go there) Do not confuse the C7 with the CM7 (C major 7). Here is a brilliant walk-through on Seventh Chords if you are still a little foggy.

Now, go back to the "Somewhere Over The Rainbow" example and try to identify the chords. You should have all the tools needed to spell out each of these chords no problem! With just this limited understanding of these five basic chords (major, minor, major 7, minor 7, dominant 7), you can figure out the notes for most of pop music ever written ever. Ever. Test yourself! See if you can figure out these five chords in every key! Make it a game, start with your favorites, or make a plan to learn these five basic chords in 2 new keys every day. You'll be astounded by how quickly chord symbols will become second nature to you!

In my next post, I'll dig a little deeper into chord symbols and talk about suspensions ("sus chords") and other fun sprinkles we can add on top of our basic chords... but for now, I'll leave you in "suspense"!

Coty Cockrell is a freelance musician and artist living in Brooklyn, New York working as a professional ballet accompanist, theatrical music director, and vocal coach. When not teaching private lessons, he gigs with his jazz trio throughout the NYC area.

To inquire about booking or to schedule a trial piano or vocal lesson, please visit the Contact page.

First Day of Spring

Spring has Sprung! Well... sort of. It was a snowy one up here in New York. While it was quite a sloppy schlepp, I still managed to celebrate National Macaron Day! Hopefully, warm and sunny photos will soon follow.

Spring has Sprung! Well... sort of. It was a snowy one up here in New York. While it was quite a sloppy schlepp, I still managed to celebrate National Macaron Day! Hopefully, warm and sunny photos will soon follow.

Daily Slice - Thursday, March 19th

Sometimes people ask me what a typical day is like, being a freelance musician/artist in New York City. The short answer is, there's no such thing as a typical day. I'm sure my freelancer readers can agree, the same parts of this lifestyle that give you freedom, variety, and excitement can also be stressful and nerve-wracking. How do you know how much money you'll make if your job flow fluctuates? How do you plan events, vacations, or just life?

Sometimes people ask me what a typical day is like, being a freelance musician/artist in New York City. The short answer is, there's no such thing as a typical day. I'm sure my freelancer readers can agree, the same parts of this lifestyle that give you freedom, variety, and excitement can also be stressful and nerve-wracking. How do you know how much money you'll make if your job flow fluctuates? How do you plan events, vacations, or just life?

Well... I'm still figuring all that out. There are plenty of people way smarter than me who have advice on budgeting for freelancers, but that's not what this post is about. I'm going to share with you a cross-section of my life, one little slice at a time.

Since Dance Theater of Harlem is gearing up for their New York season, I have started playing morning classes again. Class starts at 9:30am, so that means I should leave the house a little after 8:00 so I can get a cup of coffee. The morning commute goes a little smoother for the caffeinated. Also, it never fails that the day you're running late, the trains are delayed. Damn Murphy and his stupid Law.

At 8:15am I'm dashing out the door with my coat, scarf, and gloves. It's still pretty cold out, and a ten minute walk to the subway won't be fun if I'm not dressed properly. I've got a small carry-all bag that I got from the military surplus store. It contains: a handful of protein bars and other snacks (you're not you when you're hungry), one of my portable knitting projects (cabled socks that will probably never be finished, they just like to ride around the city with me), headphones (essential), Tums/Advil (you never know), and my phone charger. If your phone dies, you're toast -- beyond checking Facebook endlessly, it's vital to be able to answer emails, calls, and texts on the go. The world is your office! Well, except for the subway (no reception). I may not be coming back home until nighttime, so I need to make sure I have everything with me I might need.

At 9:05am I get off the train at 145th street. No cash. I'll have to pass up my usual 75¢ bodega coffee. ("What's a bodega," you ask? See the brilliant illustration below!) Fortunately, there's a new Ethiopian cafe that has incredible coffee... and I can use my card. I get the big one.

9:30am. I'm settled into class in the upstairs studio at DTH. The ceiling is tall and has skylights, and the sun is streaming in on the warm brick walls. The teacher is a guest artist who danced with the Royal New Zealand Ballet; he is quick and efficient, yet relaxed and disarming. There is a film crew.

By 11:05am I am walking out of the studio toward the subway. My next engagement is at 1:00pm, so I have plenty of time for lunch and a spare errand, but not much else. I take the 1 train to 72nd street and find an Indian restaurant with a lunch special. Bingo. Sunny spot, vegetarian platter, life is good.

Halfway through lunch I get a text from a young lady who needs to submit a filmed audition for a theatrical project, and needs an accompanist. After much discussion we decide on a time and place. My original plan was to head home in the afternoon and teach a piano lesson at 4:00pm, but now all of that is rearranged so that we can use a rental studio space in town. I head toward my next class and leave her to set up the details.

1:00pm. I am warming up on the grand piano in the corner of the studio on the third floor of Steps. My window overlooks Broadway and is right above a hectic grocery store. It seems an ambulance or fire truck always goes by during this time; the morning coffee helps me stay focused, but it's tempting to gaze out the windows at the tall buildings and the bustling traffic. I play through waltzes and mazurkas, polonaises and adagios. The time flies by.

My original plan was to head home, but at 2:30pm I'm faced with a decision: go home to Brooklyn and come back to Manhattan later, or just hang out somewhere for four hours. It's a nice day out, so I choose the latter. I decide to stay on the west side of town and take the 3 train to 14th street. I meander down through the west village, peeking into hidden gardens and terraces as I wind through the convoluted jumble of streets. I pass by designer boutiques, an old-fashioned soda shop, an episcopal church, a candy store, another episcopal church. I shudder to think what these quaint, almost provincial-style homes cost in this neighborhood. A mainstay for this neighborhood, McNulty's Tea and Coffee, lures me in. The robust aroma of freshly roasted coffee compels me to leave with a half pound of the custom blended Vienna Blend. A few blocks away I spot a cafe that features live music; I go in and get the contact info for booking. There is a small stage in the back with an upright piano.

3:35pm. I make my way west until I get to the waterfront. It's still quite cool in the shade, but nice in the sunshine. I walk along the riverfront park for several streets, gazing at the bright reflective water between piers. I sit down and do a bit of writing, more coordinating for the lessons this evening. What a beautiful office.

At 4:00pm I head back toward NYU and arrive at 100 Montaditos, a Spanish restaurant that features several small sandwiches (100 of them, to be exact). After a few mini sandwiches, I'm dreaming of warm weather and trying to ignore thoughts of the impending snow tomorrow.

5:00pm and my phone battery is perilously low. I duck into a Starbucks, which are ubiquitous in NYC, and find a corner spot near an outlet. The outlet doesn't work. I abandon the plan and head toward the studio.

I get to Pearl Studios around 5:30pm, an hour before my scheduled appointment. The rehearsal room is on the 12th floor in studio J. The room is much bigger than I thought it would be, with folding tables and a mirrored wall. An upright piano is in the corner of the room; it is in relatively good shape, but could desperately use a tuning. I whip out my charger and plug in my phone, without a moment to spare. Crisis averted. With an hour to kill, I pull out my sock project and make considerable progress.

My piano student arrives at 6:30pm for her first lesson. Aside from the dismal state of the piano's upper register, the lesson goes swimmingly. The coaching/recording session scheduled immediately after goes off largely without a hitch, save for running out of time. Promptly at 8:00pm, the next clients walk into the rehearsal room, which is our clue to leave. At 8:05pm I head to Penn Station to catch a Queens-bound E train, and finally head home.

I walk in the door at 8:45pm, throw my things on the table in the corner and start a lot for tea. There are still a few emails to respond to, and a few lyrics I've been wanting to try at the piano. The next day will be very different from this one, with a morning class at the beautiful New York City Center and a huge break before evening classes on the upper east side. If I can fit in time to check out the Björk exhibit at MoMA and do laundry, it will be a productive end of a "work week" (I have more work on Saturday).

Freelancing can be panic-inducing, but when work is steady it can be remarkably freeing if you frame the work in the right mindset. Appointments and obligations are the anchor of my daily schedule, and I fill in the cracks depending on where I am in the City. With NYC being such a dense and diverse metropolitan area, it's easy to find something to explore or some cozy spot to hang out no matter where you are... as long as you're prepared for adventure.

Coty Cockrell is a freelance musician and artist living in Brooklyn, New York. He is actively involved in the dance world as a professional ballet accompanist, and also works as a theatrical music director and vocal coach. When not teaching private lessons, he gigs with his jazz trio throughout the NYC area.

To inquire about booking or to schedule a trial lesson, please visit the Contact page:

Sound and Vision

You tell someone you have "synesthesia" and chances are, they'll take a step back and ask if you're contagious. The first time I'd even heard this word was in my tenth grade advanced English class. Meaning "the blending of the senses," synesthesia referred to the literary phenomenon of combining two different sensory experiences into one -- a "blue note" or a "sour look," for instance.

You tell someone you have "synesthesia" and chances are, they'll take a step back and ask if you're contagious. The first time I'd even heard this word was in my tenth grade advanced English class. Meaning "the blending of the senses," synesthesia referred to the literary phenomenon of combining two different sensory experiences into one -- a "blue note" or a "sour look," for instance.

While I had never heard this luxuriously fancy word before, this concept felt right at home to me. As a kid I was intensely interested in music, art, and language. My mother even tells me that I knew the correct order of the spectrum at 18 months old, according to some ancient crayon drawings. I chalk this one up to the pervasiveness of Polaroid video tape sleeves in our household. Even so, did this early exploration of art and color give me some sort of creative superpowers where I can "hear" colors, or "see" music?

I should give you a little bit of background on synesthesia based on some research I've done over the past few years. There are several documented types of synesthesia, but it seems that each occurrence can be very uniquely personal. While color/sound or color/music synesthesia is common (also called "chromesthesia"), there are several other pairings, like texture/taste (where a smooth, marble surface may elicit a minty taste), or typographical/color (where certain characters are specific colors, for instance).

Some research implies that synesthesia "develops during childhood at the time at which children are for the first time intensively engaged with abstract concepts. This... explains why the most common forms of synesthesia are grapheme-color, spatial sequence and number form: These are usually the first abstract concepts that educational systems require kids to learn." Early in a child's development, neural pathways are forged in the brain, making new connections. The more that these pathways are used, the stronger the connections become. I would argue that if a child were engaged in a number of different sensory activities at an early age, especially multisensory activities that encouraged the exploration of abstract ideas, that child could experience synesthesia. Music practice combines concepts of aural skills and mathematics; early piano lessons specifically add a pictorial element, often with musical notes or finger positions denoted by color-coding.

My dear friend Nicole, a beautifully gifted writer and all-around incredible human being, has a unique pairing where each letter seems to have a specific personality. "I associate gender strongly, then age, and sometimes colors with letters and numbers. I also do the geometric visual image of time that some people with synesthesia do," she says. In this way (as I understand it), some words just tend to "get along" better than others. Is it possible that her typographical/personality association influenced her writing career? Or that my particular brand of synesthesia, where musical tonalities (or keys) are accompanied by a specific color and mood, influenced my career as a musician and artist?

The first memory I can recall vividly experiencing the color/music connection was during my high school years. I had won tickets to hear a string quartet perform on the campus of the University of Alabama at Huntsville. I can't remember now what the program was, but I do remember how lush the harmonies were. The music was so mellow and expressive it just seemed to wash over me.

The American composer Aaron Copland, in his book What to Listen for in Music, describes three ways of listening to music: the sensuous plane, the expressive plane, and the musical plane:

“The sensuous level, or plane, is the most basic, but pleasurable level of enjoyment. This level of listening requires the least amount of brain power; therefore we usually engage this level when we use music as background music-to fill the silence in the room. The expressive level requires some concentration, for we can feel some sort of emotion from the music. We may not be able to specify what we feel, but we know it is there. Then there is the third level, the sheerly musical level. Most people do not reach this level, which consists of the notes themselves and their manipulation. Professional musicians are quite aware of this level, but so much so that they lose the ability to enjoy it on the sensuous level. These levels are not used separately; instead all three levels of listening to music contribute to the musical experience.”

As I leaned back in my comfy, ochre-colored seat, I sort of started to zone out. Not that my mind was wandering, but rather that my thoughts were very still; I was actively listening, and an active participant in the moment I was in. Gradually, I began to perceive waves of color, almost like an aurora undulating and shifting in front of my field of vision. The wispy shapes of translucent color seemed to change with the character of the music; the whole experience was something like a lucid dream. When the piece finished, the shifting layers of color lingered and faded a bit, and then vanished as the audience roared with applause.

What. Was. That.

I figured it was a daydream. Maybe I was experiencing music on another level? It wasn't until I was in college that I began understand what was going on.

I was in aural skills class, my favorite course that semester. My friends thought I was a freak because basically everyone hates aural skills. It involves sight-singing, ear-training (learning to identify chords and intervals purely by ear), and dictation (writing down music that is played). Due to the intangible nature of the concepts studied, it can be a fairly stressful class. My teacher Dr. Hardin, being the funny guy that he was, liked to play to the general terror of the class. One morning he stood behind the tall upright piano at the front of the room, slammed down on a random chord and said "Pop quiz! What key is this?"

He chuckled as the class was agape at this stupidly impossible little test. Being a bit of a smart ass, I shouted out "B-flat major!"

His face dropped. "Did you say B-flat?"

"Ummmm... yeah?" He played another one.

"G major?" And another one. "D-flat." And another. "A major!"

He played each chord so quickly, and it seemed so absurd to even attempt a guess, I just blurted out the first thing that came to mind. At this point, I realized that the whole room was staring at me like I had E.S.P. What was going on?

My classmates assumed I had perfect pitch. I really don't think that is true (although it would be a convenient party trick). I certainly wasn't clever enough to "count" up or down in my head that quickly to try to figure out what key the chords were in, there just wasn't enough time. The only explanation I have is color.

To illustrate what I'm getting at, imagine biting into a fresh, ripe apple. What senses are associated with this? The brilliant, shiny red hue of the apple skin; the cold smooth texture; the crisp, cracking sound it makes when you bite into it; the sweet, slightly drippy flavor of the apple flesh: all these senses are so distinct and so different, but each one equally valid.

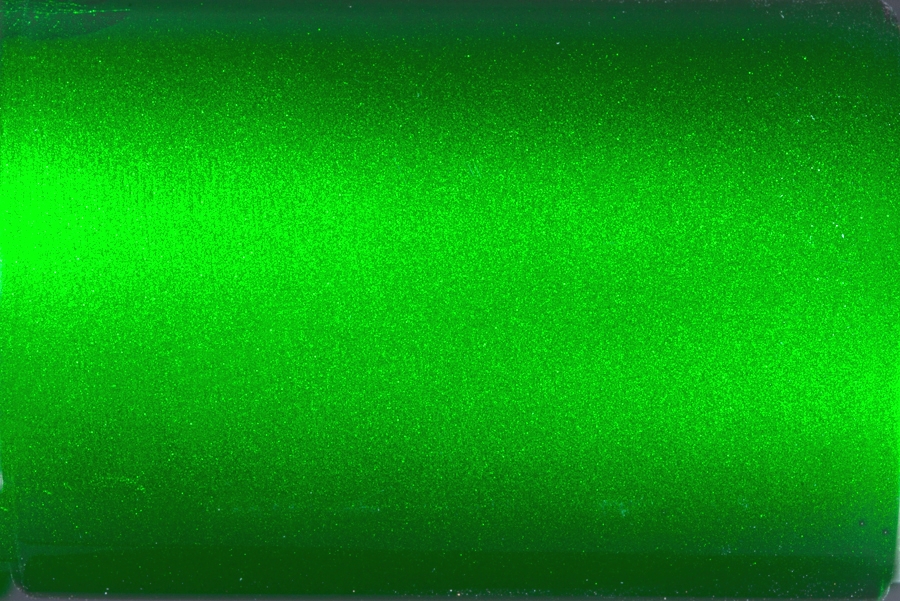

Now imagine if a musical chord or note could elicit an equally strong but different sensation, just like the apple tasting tart and hearing the crack of biting into it. That is what was happening. D-flat Major was a ripe and juicy, deep purple... like a plum. F Major was vivid and spritely, the color of a "Jungle Green" crayon. B Major and F-sharp Major were pale, almost metallic kinds of colors: silvery titanium and translucent lilac, respectively.

This isn't to say that I necessarily saw those colors like a hallucination, but that they resonated with me. Just like biting into an apple, and tasting how crisp and tart it is. Imagine how jarring it would be to bite into an apple, and instead it was juicy and tasted like an orange! With each chord played on the piano, I had an instantaneous revelation of the key... as obvious as if he had held up a giant piece of different colored paper for each one. It was just D-flat Major, because D-flat Major is purple and that's what it was.

A few days after describing the event in another class, a fellow classmate Aurelia thoughtfully presented me with a small stack of papers: well over thirty pages of info all about synesthesia. It seemed like we had a few things in common, and I couldn't wait to dig through this new resource.

Flipping through the pages, I was amazed by the number of revolutionary musicians throughout history who claimed to have synesthesia: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Amy Beach, Jean Sibelius, and Duke Ellington, just to name a few. There were lists that detailed which colors were linked to each key or note. The lists were startlingly different, and varied by how complete they were. Many even related keys to lightness and darkness, and some related color to "tone color" or "timbre" (i.e. the same tone played on contrasting instruments). Naturally, I started comparing my perceptions with those written in front of me.

I've tried to come up with a color that goes with each major key, but sometimes it's difficult to express color and mood in one image. For instance, A Major is a warm, almost dusty color, like an old violin, or morning rays of sunlight streaming through a window onto a hardwood floor. E-flat Major is blue and round, like a pure water droplet splashing into a still pool in a crystal cavern. B Major has an iridescent shimmer, while B-flat Major has a deeper, satiny luster. C Major is red, like Italian "red sauce": hearty and well-balanced, but not too serious -- all-purpose and adaptable. G Major is a little more outgoing, sort of citrusy like a tangerine, while D Major had a gentler, calmer warmth -- like the sun breaking through clouds at sunrise, or the glowing, smoking embers of a campfire at dawn. To me, each key seems to be its own little universe; each one has its own personality. Sure, music played D Major can be dark or brooding, but it really seems to "resonate" more for me as a warmer, brighter feeling.

After years of exploring the overlap between color and music, I have only come up with more questions and possibilities. My first was whether there was a general theme in other synesthetics' interpretations. Although the color schemes were very different, there seemed to be a general consensus that higher notes were brighter, and lower notes were darker. In addition, most musicians also included additional descriptors other than just pure chroma; For Rimsky-Korsakov, certain keys were "clear" or translucent (A Major was "clear, pink" while F Major was "clear, color of greenery") and others hardly had any chroma information at all (D-flat was "darkish and warm" and B-flat was simply "darkish").

Although it seemed that color systems were very different from person to person, I wondered if there was some other overarching, unexplored reason why certain colors would resonate strongly with specific tonalities. I noticed that my color scheme had some significant overlaps with the visual spectrum, starting with a C Major scale. C was red, D was orangish, E was a bright yellow (with a tinge of chartreuse), F was vivid green. Was this merely an artifact from my own knowledge of the spectrum (similar to the bouba/kiki effect), lined up with middle C functioning as a convenient starting position? Why, then, did the similarity stop after that? G Major should have been blue, and A Major purple.

Every high school student knows that sound moves in a waveform (at least they should), and that the electromagnetic spectrum contains everything from radio waves up to gamma rays, including the visible light spectrum. I knew that the standard tuning pitch is A440, which means that the A above middle C is tuned to exactly 440 Hz. An octave above that would be A880 (it is doubled), and an octave below that would be A220. Musical tone, therefore, was essentially just a soundwave that vibrated, or "resonated", at a specific frequency. (The video below excellently visualizes how different frequencies affect resonance patterns in a material) If a musical tone's frequency could be proportionally intensified until it reached the energy in the visual spectrum, what would the resulting color be? Is this even possible, are these different types of waves?

Aside from scientific speculation, there are even similarities in terminology in music and art. Some of the fundamental principles of art are harmony and rhythm. And in the music world, the term "chromatic scale" (meaning a scale with twelve notes, each one a half-step above or below the next) has the root word chroma, meaning "purity or intensity of color". Do we connect music and color simply because they have long been described this way? The term "color" even dates back in usage to the medieval era!

I would one day love to take part in research that investigates some of these questions in greater detail. I would like to explore an idea that composer Alexander Scriabin developed: the Clavier à lumières, or "keyboard with lights". In Scriabin's invention, each musical note is represented by a specific color. The color scheme was based largely on Sir Isaac Newton's Optics, as it is doubted that Scriabin was himself synesthetic. Using MIDI technology, I would be fascinated to develop an instrument that would display a color representation of the music played via projection. A computer program would analyze the notes played and place them in a key, with higher pitches represented as lighter colors and lower pitches as darker colors. Volume would be interpreted by brightness or intensity of hue. Still, there would be several theoretical problems to work out. For instance, what would happen if two different chords were played at the same time? Would the colors be mixed together, like two colors of paint? Would they simply exist side by side, like two pieces of colored paper?

Regardless of whether you perceive music with the addition of color, Aaron Copland encourages all people to actively engage themselves in the act of listening. Whether you understand the intricate inner-workings of music theory or simply love music because of how it makes you feel, music is fundamentally an artistic expression -- an intellectual, emotional, and spiritual expression of something that is greater than us all, connecting us all.

This evening I leave you with one of my favorite videos, Beck's creative reimagining of a David Bowie classic Sound and Vision. Please enjoy, and until next time, stay squirrelly.

The Theory of Musicality - Learn Piano like a Rockstar

It never fails - every time I take on new piano students (especially teens and adults) the primary reason they want lessons is so they can play the music that they love. Church hymns, pop music, show tunes, even budding songwriters who want to bolster their instrumental performance skills. I am totally inspired by these new, eager students! Their drive, their vision... there's no better reason to make music than because you love it.

I usually start out the first session with an informal chat about their goals with piano, what they want to get out of private lessons. Their eyes light up as they describe themselves performing the music that they are passionate about.

It never fails - every time I take on new piano students (especially teens and adults) the primary reason they want lessons is so they can play the music that they love. Church hymns, pop music, show tunes, even budding songwriters who want to bolster their instrumental performance skills. I am totally inspired by these new, eager students! Their drive, their vision... there's no better reason to make music than because you love it.

I usually start out the first session with an informal chat about their goals with piano, what they want to get out of private lessons. Their eyes light up as they describe themselves performing the music that they are passionate about.

There's also a common backstory, an all-too-familiar tale of childhood piano lessons (sometimes for ten years or more), but they just didn't stick. An old-fashioned, curmudgeonly piano teacher who stuck to outdated method books is usually in the equation somewhere.

When I first began teaching, I defensively clung to the structure of technique: scales, music theory, method books, and a regimented approach to my favorite instrument. Unsurprisingly, many students began to fall off due to lack of interest. I thought, how can you play complicated music if you haven't mastered the basics first? I found myself caught between a responsibility to teach classical technique and music theory, and a pressure to indulge the student's initial impulse to dive into the music head-first, knowing that it would be an uphill climb.

That is, until I realized that the two didn't have to be mutually exclusive.

A few years ago, I was having a conversation with Ben Lassiter, a good friend of mine and a remarkable guitarist and educator. As we were each talking about our students, he mentioned a six year old who was really excelling at a remarkable rate. He had already learned several songs and chords, and was able to take that basic knowledge and even expand on it at home. I thought back to my piano students, many who were struggling to move past even the most basic exercises. What was the breakdown?

I asked him about his process when teaching a new student. To my surprise, he seemed to have a very similar approach as I did, asking them what kind of music they wanted to play. The major difference, however, was that he actually incorporated pop music into the curriculum first!

But how do you go from being a total beginner to playing the hits on the radio?

The answer was so simple: one chord at a time. He explained that when starting out, they'd pick a song together, usually something popular and simple. In pop music, there is no shortage of "three chord songs", so with only three chords to learn and an almost infinite number of songs out there, the scope was manageable and exciting.

Sure, scales and arpeggios and other minutia of technique would come in good time. But this approach also changes the role of teacher from "master" to "guide", merely opening the door for the student so that he can gain the basic tools needed to explore his musical world. From the Beatles to Taylor Swift, Ben's students would eagerly go through song after song, unknowingly developing more sophisticated skills like rhythm and counting, subdividing, harmony, and song form. They would learn the various chords in a song, then put them into practice right away. Sometimes they would even sing along! It was an ingenious method, and I sort of hated him for how laid-back and relaxed he made the whole thing sound.

If it could work so well for guitar, what about piano?

I was able to test my theory with a bright young lady who began studying with me. At thirteen years old she had already been taking piano for a few years. I could tell that she enjoyed playing, but had reached an age where she was starting to become bored with the method books and short pieces she had been given up until then.

At the start of one lesson, rather than have her play through her assigned piece I asked her what music was on her iPod. Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, One Direction, Adele, Bruno Mars... once she started listing off names, she almost tripped over herself getting to the next one! This girl LOVED music, but was somehow disconnected from it in her own lessons! It was almost like her piano lessons had nothing to do with her inherent passion for her own music.

So I went out on a very precarious limb: I asked her if she'd like to play some of that stuff in her lesson, not just the stuff from the book.

I thought she was going to somersault off the bench.

The first song we looked at was "Rolling In The Deep" by Adele. I pulled up the chord changes from a guitar tablature website and began writing them out on a piece of staff paper. She was excited, and intensely curious. This quiet little girl, who had such a lovely smile but would rather fade into the wallpaper if she could, was asking question after question, pointing to the paper and eagerly trying to figure out what these strange hieroglyphics meant.

As I started to show her how to interpret each chord, that when you see "Dm" that means to play D-F-A all together, the questions started rolling in. "How come that's not D Major? So the little 'm' stands for minor? What if it WAS D Major? What would the... the 'chord symbol'? What would it say if it was major? What does that seven mean?"

It was astounding. Rather than lecturing, almost by rote, that the dominant seven chord falls on the fifth scale degree, she was learning it on her own. Willingly. Eagerly. Sure, a dominant chord just sounded right, but she still wanted to know why. So we drew out a major scale and began to dive into the theory of WHY the dominant seven chord is spelled like it is, and why certain chords were major and certain ones were minor. All of this from a three-chord pop song, with no method or theory book.

For her homework, I gave her another song, and told her to write out the chords and practice playing them.

Fast-forward a few months: she maintained some classical repertoire in her studies, but retained it much better because she better understood the harmony behind the notes. She also whizzed through pop song after pop song, expanding into classic hits and even a few jazz standards. Her understanding of chords continued to develop, and she even became involved as the keyboardist for a small rock band comprised of students her age!

This approach works because the music comes first. Developing good technique is super important, and mastering technique and music theory takes time. However, if you don't have passion to keep driving you forward, you'll never stick around long enough to get the chance.

In future posts, I'll be digging deeper into the specifics of understanding chord symbols, and how to use them to get you closer to what you truly care about: the music you want to play.

Thanks for reading. And until next time, stay squirrelly.

Ben Lassiter lives in Durham, North Carolina, where he shares his rockstar talent with students from seven years old to adults. He has a master's degree in Jazz Studies from North Carolina Central University with an emphasis in Composition and Arranging. He also plays in the nationally renowned swing ensemble, The Mint Julep Jazz Band.

Check him out at his website, www.benjaminlassiter.com.

A Little Wishful Thinking

Summertime will be here soon enough, but we're still stepping over greasy, frozen slush piles up here in New York. As I was accompanying my ballet class this afternoon, watching the warm sunbeams creep through the skyscrapers and land gently across the studio floor, I just couldn't help myself.

I hope this gets you through the last push until spring!

At the Piano Barre - My Unlikely Beginning as a Ballet Pianist

I got thrown into accompanying ballet classes with absolutely no experience, and no idea what I was doing. I suppose that's the best way to start something brand new -- otherwise, you'd be scared to death and crippled by the thousands of ways you could fail in a tragic, blazing shame spiral. Better to just plunge right in and cling to the surprisingly powerful shield of ignorant positivity, I always say. Well, at least that's what I thought that day.

I got thrown into accompanying ballet classes with absolutely no experience, and no idea what I was doing. I suppose that's the best way to start something brand new -- otherwise, you'd be scared to death and crippled by the thousands of ways you could fail in a tragic, blazing shame spiral. Better to just plunge right in and cling to the surprisingly powerful shield of ignorant positivity, I always say. Well, at least that's what I thought that day.

It was the first day of a high-caliber, three-week long performing arts intensive. I learned that morning that I would be accompanying the ballet auditions. Hundreds of incredible dancers from around the world squeezing into a mob of black spandex and pink frilly bits against the back wall of a huge studio with soaring ceilings and pristine mirrors. What was I even doing? How did I get here? What am I supposed to play? What is this strange made-up language that the Lord of the Dance is shouting to the throngs... is that French? Oh god, I failed French. They didn't tell me French would be involved!

Apparently, the "Lord of the Dance" is someone else entirely, and this guy is called the "ballet master" (which sounds WAY cooler, in my humble opinion). As he demonstrated the various movements, passing through positions and poses like a graceful robot (unlike the terrifying animatronic monstrosities I grew up with at Showbiz Pizza), the mass of dancers eagerly mimicked his every move down to the slight flick of the wrist, the subtle tilt of the head.

It was entrancing, and a little creepy.

And then he looked at me. I can't even remember what I played. I think it was something hinting at Chopin, but before I knew it they had all stopped, so I did too. And then they changed lines and did it all over again. I breathed. I played. Well, that wasn't so bad... It was actually kind of fun!

Over the course of the day, I began to understand how to feel the pulse of the dancers, whether they needed something in three or in four, slow or fast, light and crisp or lush and moving. I started to anticipate the character of the combination, and feverishly searched my brain for fragments of melodies I could throw in to liven up the audition. Something to make the dance faculty crack a smile (which was very hard to do), something to make these hurried, nervous dancers relax and put their best foot forward (pun totally intended).

For one group, I played the opening riff from Stairway to Heaven. For another, the theme from Beauty and the Beast. A Britney Spears song. Jurassic Park. Lady Gaga. I was living for this challenge, searching the room for that knowing smile, the "gotcha" moment, when their eyes darted over to this gargantuan piano in the corner with a gleam of recognition. It was like watching popcorn pop, if you can imagine something so thrilling.

There are some really, REALLY terrific ballet accompanists out there. Pianists who know every note that Tchaikovsky ever penned, who could whip out a mazurka or polonaise with lightning speed and execute it with frightening accuracy and artistry.

That is not me.

I'm getting there, but I have a lifetime to build my repertoire of codas and adagios and petite allegros. All I knew was that this was a fun challenge, it was a creative challenge, and it was a practical challenge -- three things that don't necessarily always overlap in the piano world.

What I didn't realize then is that my musical life leading up to this moment had primed me in other areas to be an incredible ballet pianist. I started out playing piano by ear, so I took audio cues from the ballet master very well, and was great at interpreting their vocalizations into musical material. My experience in musical theater prepped me for working with dancers and choreographers, which can be a special skill for sure. My training in the jazz world left me with a brain full of chord progressions and the means for making up stuff on top of them. My classical piano degree made me keenly aware of the idiosyncrasies of various piano styles: characteristics of Bach, Mozart, Chopin, Gershwin. And my experience goofing off with my nerdy musical friends playing "the game", in which audience members would shout out contrasting songs or themes and I would have to weave them together in one seamless medley, primed me for this little inventive challenge I'd given myself.

Sometimes it worked surprisingly well. A Katy Perry song danced across the floor; a slow, expressive adagio developed over a Radiohead ballad.

Sometimes it was a glorious tragedy, seemingly eclipsing the ultimate downfalls that have beset the human race for a millennia. The fall of the ancient Roman Empire, the Hindenburg disaster, that one time Coty tried to play "Crazy Train" for pliés.

As I mentioned before, the best strategy is to charge positively and ignorantly forward, snatching up as many bits of knowledge and insight as you can. I have been very fortunate to work with incredible ballet masters who communicate eloquently and musically... and have a lot of patience.

Now, I play ballet classes, auditions, and workshops in New York City at a number of schools. I'm even the principal pianist for a professional, touring ballet company. And let me tell you, I am still learning. Every single day, every single class. Ballet babies to the mature movers (mature as in older, not that other definition).

I'm thrilled to bring my own flavor of music to each class, a culmination of my experience as a theatrical actor and music director, jazz musician, composer, and classical pianist. But more than that, in the true spirit of collaboration I love creating something that has never existed before, and will never exist ever again, encapsulated in a beautiful string of moments linked together, one beautiful movement at a time.

The birth of a website!

As I sit here at my kitchen table, it is 3:17 in the morning. I should be in bed (I should have been in bed a long time ago, actually), but I am just too delighted to have made such expeditious progress on my first professional website! This has truly been a milestone for me, a goal looming over me for years. And here it is, my very own space on the internet to share my thoughts, ideas, upcoming projects, and connect with fans, family, and fellow artists!

Please keep an eye out for updates... I'm sure that there will be several in the coming days! I have a lot of really exciting plans for this spring and summer, but will need time to work out the details.

Until then, full speed ahead!