The Theory of Musicality: Chords 201

If you’ve been keeping up with my introduction to chords and chord symbols over the past few weeks, congratulations! With a little bit of time at the piano, you should now be familiar with all these chords: Major, Minor, Major 7th, Minor 7th, Dominant 7th, Sus2, Sus4, Add2, Open 5th, and (Add)6. That’s a lot! With little more than this information, you can now open up any pop fake book and interpret most of the chords in pretty much every chart. Go you! (If you’re just now joining us, you can get totally caught up in no time by starting HERE) However, our ambitious journey doesn’t end here, we’ve only just started! This week we look at a super fun (and super easy) concept: Slash Chords.

Nope, not those kinds of Slash chords.

If you’ve been keeping up with my introduction to chords and chord symbols over the past few weeks, congratulations! With a little bit of time at the piano, you should now be familiar with all these chords: Major, Minor, Major 7th, Minor 7th, Dominant 7th, Sus2, Sus4, Add2, Open 5th, and (Add)6. That’s a lot! With little more than this information, you can now open up any pop fake book and interpret most of the chords in pretty much every chart. Go you! (If you’re just now joining us, you can get totally caught up in no time by starting HERE) However, our ambitious journey doesn’t end here, we’ve only just started! This week we look at a super fun (and super easy) concept: Slash Chords.

Before we dig into this week’s lesson, I’d like to take a minute to chat why we use chord symbols in the first place. Like we’ve touched on before, chord symbols are a musician’s form of “harmonic shorthand”; they tell the musician at a glance exactly what notes are in the harmony. But the question remains: since people already write down the notes in sheet music, why should we care about chord symbols?

tl;dr: chords are super great and helpful, but you should probably read proper sheet music too

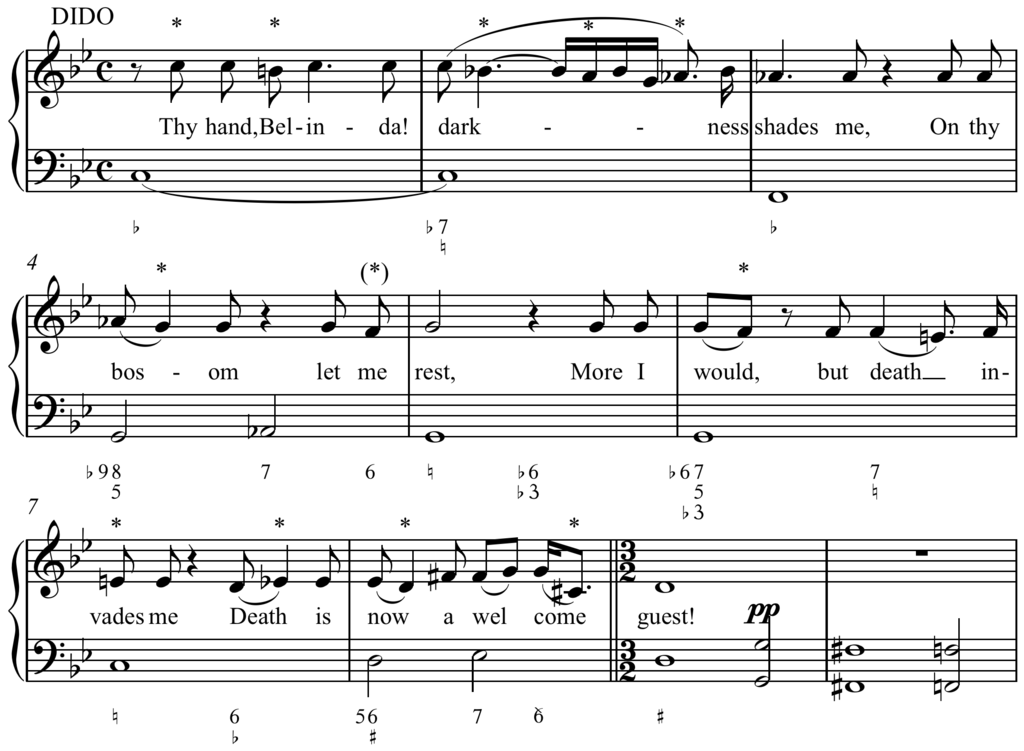

Look at all these squiggles! Ain't nobody got time for that.

Formalized music notation used in standard music notation (all those little “squiggles climbing over a fence”) is a fantastic system for writing down exactly what notes you want played, when to play them, and how long to play them for. This system developed over hundreds of years, starting with monks and scribes elaborately penning down sacred music, and evolving into the precise system we use today. Even so, it isn’t a perfect system; while it may work particularly well for Western art music (see “classical music”), it is not the best system to capture the nuances, and even more the actual practicality of music-making for countless genres of music.

Bobby McFerrin and Yo Yo Ma

Bobby McFerrin (if you don't know who that is, google him ASAP) tells a story about his cellist friend, Yo Yo Ma. Seeking to expand his knowledge of improvisation, he travelled to a remote village in Botswana to share his music, and experience the local musical culture of the people there. In one anecdote Yo Yo Ma found himself transfixed by a song that the village shaman sang for him. He quickly got out his manuscript paper to write down the tune, and asked him to repeat the song so he could ensure that he wrote it down accurately. But when the shaman repeated his song, the melody was different! McFerrin goes on to say:

“And Yo Yo is saying But that’s not the piece you sang before. The shaman laughed and said “The first time I sang it there was a herd of antelope in the distance and a cloud was passing over the sun.” So this is the part that we lost. Every time a piece of music is played, one time there is a herd of antelope, and one time there’s not. And we turn in these cookie-cutter performances. Everything is so laid down and regimented and locked-in and so rehearsed, that they squeeze the life out of it. It no longer has any life in it because no one is open to surprise, no one is open to any spontaneous event that can happen. Everything is just dictated, and this is the way it’s gonna be. I think that’s the part that we’ve lost.”

This isn't to say that formal music notation is too fussy to be practical, but that it might not be the best solution for every kind of music. After all, there's a huge musical world outside of Western art music! (Check out the segment with Bobby McFerrin here, it's a great read!)

Standard musical notation not only struggles to give a musician freedom to improvise, but it also can be very cumbersome! This is really where I find the biggest payoff for the chord symbol system: in genres like jazz, pop, and rock where exact musical arrangements may not be necessary, the chord symbol system gives freedom to the musician to more easily interpret the harmony. In layman’s speak, you’re not wrestling over trying to read a bunch of little notes, but rather getting the gist of what the harmony is, so you can actually get the notes under your fingers and spend your time playing, not squinting at squiggles.

This isn’t to say that the chord symbol method is watering-down the music. Rather, it relies on the musician’s stylistic knowledge of the genre. This is why listening is so important! If you want to play great blues licks, listen to great blues players. If you want to sing great R&B riffs, listen to great R&B singers. And for goodness sake, if you want to play great jazz solos, listen to great jazz solos.

Standard music notation is like a very elaborate recipe from an award-winning chef: Follow these instructions exactly, use the freshest ingredients, and execute the preparation well and you will get the award-winning meal you hope for. The chord symbol system follows the same pattern, but is more of a “passed down from your grandmother” sort of recipe: all of the same rules apply, but you have more freedom to mix things up… provided that you know the basics first. You don't want to disappoint your grandmother, so you better practice rocking out with your chords.

With all that said, let’s roll our sleeves up and get into today’s topic, slash chords! In the most simple sense, a slash chord is just a chord played in the right hand, with a note other than the root played in the left. That’s it. Seriously.

In all of our previous examples, we’ve been looking at how chords are constructed in the treble clef (piano, right hand). They have all been in root position, meaning that the root of the chord is the lowest note in the chord. For a C major 7, that means that we would start with the C on the bottom, followed by E, G, and B stacked right on top. But what about the left hand? Up until now, the left hand would simply play the root note in the bass clef (left hand), which is a C. Pretty easy. What bass note would the left hand play for an Fm7 chord? You got it, an F. How about an Absus7? Ab! D7(b9 #11 b13)? If you panicked a little but said D, you are correct!

However, sometimes you might not want the bass to play the root note. If the bass is always playing the root, it can sound boring and predictable. It can also be jumpy since it has to hop around all over the place! With slash chords, you can quickly and easily see what note to play in the left hand. (In a future lesson, we'll look at how slash chords can even help to simplify some really complex jazz chords into easily digestible bites! Yum!)

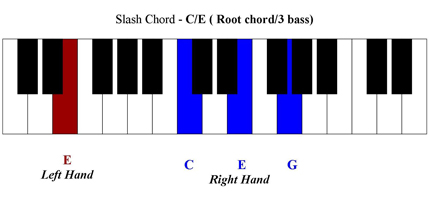

Let's look at some examples of slash chords. Below we have an example of a C/E chord. The C tells us that we are to play a C major triad in the right hand, and the part after the slash tells us to play an E in the left hand. This "C over E" chord looks like this:

When you take a chord and flip the notes up in such a way that the root is no longer the lowest note, we call that an inversion. (For more info on chord inversions, check it out here) The cool thing about slash chords is that, with the right and left hands playing together, we can get an inverted sound but still play all the right hand chords in root position. Eventually, you will find new chord voicings that you like, but when you're just starting out it is so much easier to think of chords in root position.

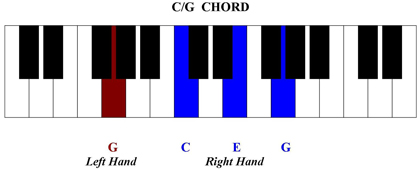

What happens if we put the next note in our chord on the bottom? What would we call it?

Why, a C/G! C major triad in the right hand, G in the left hand.

Now let's look at a chord with four notes in it:

Inversions of a C7 chord

In this example, we've taken a C7 chord and simply inverted it, each time taking the bottom note and moving it to the top.

In these three examples, we are just using the other chord tones to play in the left hand. But be creative! You can really play anything in the left hand and make it a slash chord. Depending on how the notes sound together, you may get a combo that creates tension or release. Depending on the bass note that you add, you may actually create a new chord altogether! Check out this example:

Slash chords, and the composite chords they create

Some of these combinations create some fairly advanced chords, but there are a few that we can understand at this point in time. Check out the Eb/C chord. The first thing to look at is the root in the left hand. We know that it's something over C, whether it's a C chord or not. Keep that in your back pocket for now.

Now look at the right hand. That low Bb is doubled, so we can ignore it. What's left is a perfectly stacked Eb Major triad: Eb, G, and Bb. Now, let's put those things together! C on the bottom, then Eb, G, and Bb on top. What does that sound like? A Cm7 chord! Check out some of the other chords and see if you can recognize any other similarities with chords you already know!

Now it's your turn! Find some music that has slash chords in it and go to town! Or you can get even more creative by discovering your own slash chords! Start with a triad in your right hand and the root in your left, and just try different root notes! Walk your left hand up and down, trying all the white and black notes with your triad until you get to a sound you like. What chord is that, what is it called? C/Ab, D/C... even try bigger chords like BbM7/C, EbM7/C, D7/E... have fun! Keep a notebook, writing down your favorite combos, I want to hear all about it in the comments!

Coty Cockrell is a freelance musician and artist living in Brooklyn, New York working as a jazz pianist/singer, professional ballet accompanist, theatrical music director, and vocal coach. When not teaching private lessons, he performs in the NYC area as well as internationally.

To inquire about booking or to schedule a trial piano or vocal lesson, please visit the Contact page.

The Theory of Musicality: Chords 102

In my last post, we kicked off our journey into the land of chords and chord symbols. We talked about improvisation way back in the day (see also: Baroque Era), defined just what the heck a lead sheet was, and discussed why we even care about chord symbols in the first place. Finally, we got right down to the nitty-gritty and deciphered some chord symbols as we learned the five basic foundation chords, Major, Minor, Major 7, Minor 7, and Dominant 7. I hope you practiced at home between then and now, because today we're going to make things a little more spicy!

In my last post, we kicked off our journey into the land of chords and chord symbols. We talked about improvisation way back in the day (see also: Baroque Era), defined just what the heck a lead sheet was, and discussed why we even care about chord symbols in the first place. Finally, we got right down to the nitty-gritty and deciphered some chord symbols as we learned the five basic foundation chords, Major, Minor, Major 7, Minor 7, and Dominant 7. I hope you practiced at home between then and now, because today we're going to make things a little more spicy!

When you look inside a chord dictionary (in case you haven't already), you will find a staggeringly extensive list of chords and "voicings" (meaning what order the notes are played in, top to bottom). These massively dense reference books can be unwieldy and overwhelming. The reason I bring this up now is to note that we are focusing on some of the most common chords first, then expanding our focus to the more advanced chords later. Stick around long enough and you'll learn some truly fun chords, like half-diminshed 7, or flat 9/sharp 13!

Our good ol', trusty C Major triad, in root position

Let's look at a simple major triad to start, shown above. For consistency, we'll stay in the reference key of C Major just like we did in the previous entry. In switching between major and minor, we changed the third of the chord to either a major third or a minor third. But what happens if we move that note around a bit more? Let's shift that middle note down a bit.

One halfstep and we have C Minor...

C Minor, in root position

...but what happens if we go down one more halfstep?

C2, or Csus2, in root position

This chord is called a Csus2, or sometimes simply C2 for short. The "sus" is short for "suspension", and it refers to how a note likes to resolve. In earlier music, these notes (in this case, the second scale degree) created tension, and were usually resolved by moving them up or down to the closest chord tone. In this case, that would most likely be the third of the chord, or E. In classical music, this sort of relationship would be called a "2 3 suspension". (For more info on nonharmonic tones, check out this handy study guide from the nice people over at Georgetown University)

However, in modern music a composers often prefer the slightly unresolved sound of a sus chord and might not necessarily need it to resolve. By not including a third of any kind (neither major nor minor), the chord takes on an ambiguous, transient quality. Stable because of the root and perfect fifth, but somewhat undefined. Personally, I love sus2 chords.

If you keep moving the middle note down another halfstep, you get a SUPER crunchy chord that, to my knowledge, does not have a name. We're gonna just call it some kind of "cluster chord", turn around and head back.

If you shift the middle note of a major chord up by a halfstep, we come to our next new chord, the sus4 (often just called a "sus" because of its commonality).

Csus or Csus4, in root position

The sus4 chord is super common, and the middle note loves to resolve down from the fourth scale degree to the third. Sometimes it even pops over to the second scale degree before coming back up to the third to stay (we hope). Since the "4 3 suspension" sound is so incredibly common, you will likely see this chord written both as Csus4 as well as simply Csus. The sus4 has a similarly transient sound as the sus2, but because the middle note is only a halfstep away from resolving down to a major chord, our ear tends to give this chord a bit more sense tension. Even so, it certainly isn't uncommon for composers to use this suspended sound as homebase, especially in jazz.

If you keep moving the middle note up, the chord also gets SUPER CRUNCHY just like before because of the halfstep between the middle and (this time) the top notes. You can name this chord if you like! Send me $50 and the "Jeff Chord" could be a reality.

Just by moving the middle note around in a basic triad, we can have a Sus2 chord, a Minor chord, a Major chord, or a Sus4. Neat! Now let's see what happens if we start adding notes to our major triad.

In the previous lesson, when we added notes to a triad we added the seventh. Let's look at some common additions that aren't seventh chords:

Cadd2, in root position

If you add the 2nd scale degree to a C Major Triad, you get a Cadd2 chord. You can do the same to a minor chord, although I can't say that I've often seen a C Minor Add2 chord in the wild.

If you add the 4th scale degree to a C Major Triad, you get another crunchy chord (due to the halfstep between the E and the F). In recent years, I have really grown to appreciate the tension that is produced by this kind of sound, but for our purposes this is another cluster chord.

The other major Add-type chord we're going to look at today is the C6. This chord is nice and stable, but has a little bit more pizzazz than a regular major triad... sort of like a major triad with sequins. Note: It's called a C6, not a Cadd6. It's just a regular old C major chord with the 6th added. It can also be minor, called (you guessed it) a Cm6.

Since we're only really dealing with "diatonic" notes, or notes that are within the key, the only possible notes we can add to a C Major chord are D, F, A, and B. If we add the B on the top of this major triad, we come across something we've already seen before...

...a CM7. But of course, you already knew that from the last lesson!

We've thrown in an extra note and moved things all around, but what happens if we go the other way? To quote Val in The Birdcage, "Don't add! Just subtract!" This one is super easy, but warrants a bit of explanation anyhow. If you start with a C Major chord and get rid of the third altogether, you're left with a very plain, open sounding pair of notes called a C5.

C5, in root position

In the most traditional sense, this chord hardly even qualifies as a chord. We don't know if it's major or minor because there's no third! What is left is a sort of open shell, a perfect fifth interval (sometimes called an open fifth). There is a really neat explanation to why this, and other, intervals are described as being "perfect", but we'll get to that another day. Maybe.

Alright, let's wrap things up and recap! We bounced around quite a bit in this session. Let's start with what we covered last time:

Complete chord chart from Chords:101 session

Now let's add our new chords to this list! Take extra care not to get the C2, C5, and C6 mixed up! They look similar, but one has three notes, one has four notes, and one has only two notes!

Complete chord chart from both sessions, Chords:101 and Chords:102

Woah! That's a whole lot of chords! Just like last time, use this list as a decoder ring and figure out the chords in every key... or at least a few! Some of these chord names have nomenclature that is very intuitive, but some don't! I've pointed out some of the tricky ones along the way that confused me, so please let me know in the comments if you have any further questions!

Even if it makes sense to your eyes, FIND A PIANO and get your hands on these chords! I promise you, the tactile experience will help you retain this info so much easier. Start memorizing these now and you'll have no problem at all when we get to Chords:201! That's where we're going to get into some really funky chords, including slash chords! I can't wait!

Coty Cockrell is a freelance musician and artist living in Brooklyn, New York working as a jazz pianist/singer, professional ballet accompanist, theatrical music director, and vocal coach. When not teaching private lessons, he performs in the NYC area as well as internationally.

To inquire about booking or to schedule a trial piano or vocal lesson, please visit the Contact page.

The Theory of Musicality: Chords 101

I mentioned in an earlier post that I'd dive into more detail and really break down chord symbols and how to understand them, and this is the start of that journey! Once you get the basics down for how chord symbols work, it will unlock a whole new way of thinking about music! This "harmonic shorthand" is the key to quickly playing pop songs, changing the key of a song (so that it's in YOUR range), and even writing music of your own! It may seem a little tricky at first, but we're going to break it way down.

I mentioned in an earlier post that I'd dive into more detail and really break down chord symbols and how to understand them, and this is the start of that journey! Once you get the basics down for how chord symbols work, it will unlock a whole new way of thinking about music! This "harmonic shorthand" is the key to quickly playing pop songs, changing the key of a song (so that it's in YOUR range), and even writing music of your own! It may seem a little tricky at first, but we're going to break it way down.

Before we begin I should say that I am assuming that you, brave reader, have some working knowledge of musicmaking. You don't have to be a music theory wizard (unless you have a neat wizard hat), but it will be very helpful for you to understand some basics, like which notes are which on the staff, and the difference between major and minor. There are some really great music theory resources online, such as www.musictheory.net. You can also check out the iPhone app Nota, which appears to be a great, all-inclusive app for bringing you up to speed. (If you find these resources useful, or have suggestions for other resources, please leave a link in the comments! I'd love to hear about your experience!)

Gettin' down in the "Baroque and Roll" Era

So what is a chord symbol anyway? Why are they so important? Just for a moment, let's jump back in time to the Baroque era (1600-1750). In classical music at this time, it was very common for ensemble pieces to have something called a basso continuo (meaning "continuous bass"), which was simply a form of improvised accompaniment played on an instrument capable of playing chords. Since the piano had not been invented yet, that meant either a harpsichord, organ, lute, guitar, or harp would play the accompaniment. Often, another instrument would play the lowest notes, usually a cello, double bass, or bassoon. In this way, we have an instrument (or instruments) playing the bass line, and an instrument playing the harmony notes, allowing a solo instrument to play the melody on top. This basic recipe for ensemble music (bass+accompaniment+melody) has proven through the ages to be quite a successful combination.

Although most people think of modern jazz and rock music when they think of improvisation, the truth is much of Baroque music was improvised, some 300 years before mainstream popularity of jazz in America! To save the composer time and to relegate some creative freedom to the performer, a system known as "figured bass" was developed. In this system, the melody was written in the treble clef, the bass line was written in the bass clef, and a special system of numbers was used beneath the bass notes to indicate what the harmony should be. (If you want to really put on your waders and slodge into Baroque harmony, Michael Leibson's explanation on his page Thinking Music is a pretty good one.)

You don't have to understand how figured bass works (in fact, I had no clue it even existed until college) to get the big take-away: chord symbols are harmonic shorthand, and you just need to understand the language. With figured bass, the bass line was written out, making it even easier for bass instruments to play along. With that covered, the harpsichordist or lutist simply needed to fill in the rest of the harmony as it was spelled out. With modern chord symbols (and the modern piano), usually both of those tasks will be carried out by the pianist... unless you have an awesome bass player.

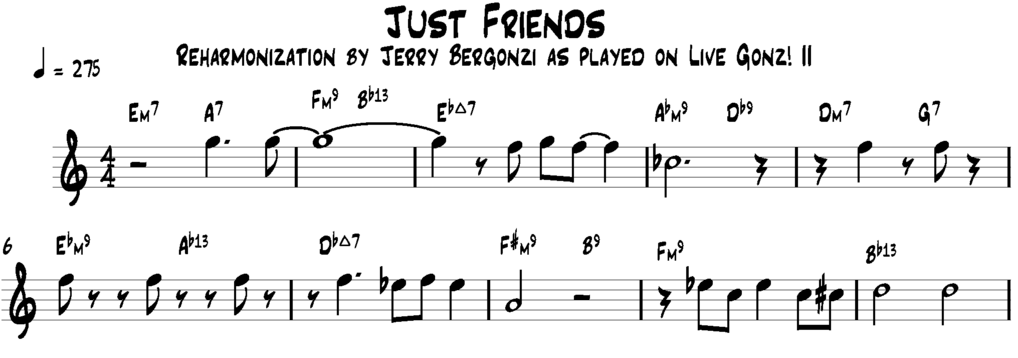

If you checked out the graphic at the top of this post, you saw an excerpt of a lead sheet called "Just Friends". A lead sheet is a shorthand version of a song; it usually contains the melody, sometimes lyrics, and chord symbols. (If you've heard about "fake books", that's what we're talking about) We're probably all familiar with melody and lyrics, so let's break down the chord symbol bit.

If you look at the example above, you'll see a mysterious little F floating above the first note. That's a chord symbol! A letter all by itself with nothing else after it tells us that it is a major chord. It's also in root position, meaning that the lowest note in the chord is an F.

The next chord symbol we see is Bb, which means we simply play a B-flat major chord underneath the melody. So far so good! Our third chord symbol is the first wacky one we've had, so let's check it out. The A means that root of the chord is A, but the next letter is a lower-case m. That means that it is minor. Since it is understood that a root all by itself is major by default, we have to add the lower-case m to indicate that it is minor. So what we have is an a minor chord... but what's with the numbers? The 7 after the m indicates that we add the minor seventh on top of this minor triad.

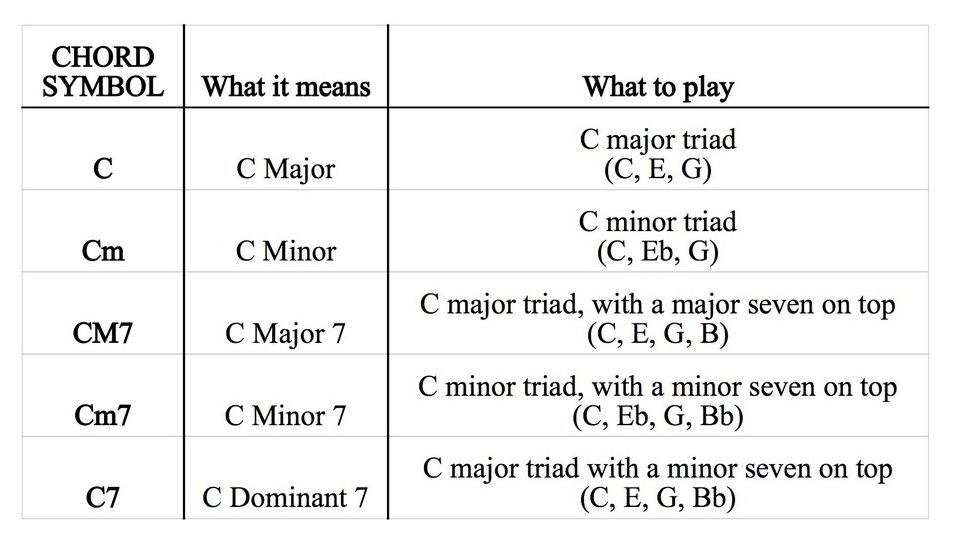

If I just lost you, don't fret: 90% of confusion with chord symbols comes from understanding 7 chords. We have a few moving parts here, so let's isolate. For the purpose of simplicity and clarity, I'll use C Major as an example.

The two factors here are whether it is a major triad or a minor triad, and whether the seventh is a major seventh or a minor seventh. Adding the appropriate 7th, a C (major chord) becomes CM7 when the major 7th is added, whereas a Cm (minor chord) becomes a Cm7 when the minor 7th is added. The only wingnut in the bunch is the dominant 7, which is just written as C7. (There's a lot of theory for why this is the norm for dominant 7th chords, but let's not go there) Do not confuse the C7 with the CM7 (C major 7). Here is a brilliant walk-through on Seventh Chords if you are still a little foggy.

Now, go back to the "Somewhere Over The Rainbow" example and try to identify the chords. You should have all the tools needed to spell out each of these chords no problem! With just this limited understanding of these five basic chords (major, minor, major 7, minor 7, dominant 7), you can figure out the notes for most of pop music ever written ever. Ever. Test yourself! See if you can figure out these five chords in every key! Make it a game, start with your favorites, or make a plan to learn these five basic chords in 2 new keys every day. You'll be astounded by how quickly chord symbols will become second nature to you!

In my next post, I'll dig a little deeper into chord symbols and talk about suspensions ("sus chords") and other fun sprinkles we can add on top of our basic chords... but for now, I'll leave you in "suspense"!

Coty Cockrell is a freelance musician and artist living in Brooklyn, New York working as a professional ballet accompanist, theatrical music director, and vocal coach. When not teaching private lessons, he gigs with his jazz trio throughout the NYC area.

To inquire about booking or to schedule a trial piano or vocal lesson, please visit the Contact page.

The Theory of Musicality - Learn Piano like a Rockstar

It never fails - every time I take on new piano students (especially teens and adults) the primary reason they want lessons is so they can play the music that they love. Church hymns, pop music, show tunes, even budding songwriters who want to bolster their instrumental performance skills. I am totally inspired by these new, eager students! Their drive, their vision... there's no better reason to make music than because you love it.

I usually start out the first session with an informal chat about their goals with piano, what they want to get out of private lessons. Their eyes light up as they describe themselves performing the music that they are passionate about.

It never fails - every time I take on new piano students (especially teens and adults) the primary reason they want lessons is so they can play the music that they love. Church hymns, pop music, show tunes, even budding songwriters who want to bolster their instrumental performance skills. I am totally inspired by these new, eager students! Their drive, their vision... there's no better reason to make music than because you love it.

I usually start out the first session with an informal chat about their goals with piano, what they want to get out of private lessons. Their eyes light up as they describe themselves performing the music that they are passionate about.

There's also a common backstory, an all-too-familiar tale of childhood piano lessons (sometimes for ten years or more), but they just didn't stick. An old-fashioned, curmudgeonly piano teacher who stuck to outdated method books is usually in the equation somewhere.

When I first began teaching, I defensively clung to the structure of technique: scales, music theory, method books, and a regimented approach to my favorite instrument. Unsurprisingly, many students began to fall off due to lack of interest. I thought, how can you play complicated music if you haven't mastered the basics first? I found myself caught between a responsibility to teach classical technique and music theory, and a pressure to indulge the student's initial impulse to dive into the music head-first, knowing that it would be an uphill climb.

That is, until I realized that the two didn't have to be mutually exclusive.

A few years ago, I was having a conversation with Ben Lassiter, a good friend of mine and a remarkable guitarist and educator. As we were each talking about our students, he mentioned a six year old who was really excelling at a remarkable rate. He had already learned several songs and chords, and was able to take that basic knowledge and even expand on it at home. I thought back to my piano students, many who were struggling to move past even the most basic exercises. What was the breakdown?

I asked him about his process when teaching a new student. To my surprise, he seemed to have a very similar approach as I did, asking them what kind of music they wanted to play. The major difference, however, was that he actually incorporated pop music into the curriculum first!

But how do you go from being a total beginner to playing the hits on the radio?

The answer was so simple: one chord at a time. He explained that when starting out, they'd pick a song together, usually something popular and simple. In pop music, there is no shortage of "three chord songs", so with only three chords to learn and an almost infinite number of songs out there, the scope was manageable and exciting.

Sure, scales and arpeggios and other minutia of technique would come in good time. But this approach also changes the role of teacher from "master" to "guide", merely opening the door for the student so that he can gain the basic tools needed to explore his musical world. From the Beatles to Taylor Swift, Ben's students would eagerly go through song after song, unknowingly developing more sophisticated skills like rhythm and counting, subdividing, harmony, and song form. They would learn the various chords in a song, then put them into practice right away. Sometimes they would even sing along! It was an ingenious method, and I sort of hated him for how laid-back and relaxed he made the whole thing sound.

If it could work so well for guitar, what about piano?

I was able to test my theory with a bright young lady who began studying with me. At thirteen years old she had already been taking piano for a few years. I could tell that she enjoyed playing, but had reached an age where she was starting to become bored with the method books and short pieces she had been given up until then.

At the start of one lesson, rather than have her play through her assigned piece I asked her what music was on her iPod. Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, One Direction, Adele, Bruno Mars... once she started listing off names, she almost tripped over herself getting to the next one! This girl LOVED music, but was somehow disconnected from it in her own lessons! It was almost like her piano lessons had nothing to do with her inherent passion for her own music.

So I went out on a very precarious limb: I asked her if she'd like to play some of that stuff in her lesson, not just the stuff from the book.

I thought she was going to somersault off the bench.

The first song we looked at was "Rolling In The Deep" by Adele. I pulled up the chord changes from a guitar tablature website and began writing them out on a piece of staff paper. She was excited, and intensely curious. This quiet little girl, who had such a lovely smile but would rather fade into the wallpaper if she could, was asking question after question, pointing to the paper and eagerly trying to figure out what these strange hieroglyphics meant.

As I started to show her how to interpret each chord, that when you see "Dm" that means to play D-F-A all together, the questions started rolling in. "How come that's not D Major? So the little 'm' stands for minor? What if it WAS D Major? What would the... the 'chord symbol'? What would it say if it was major? What does that seven mean?"

It was astounding. Rather than lecturing, almost by rote, that the dominant seven chord falls on the fifth scale degree, she was learning it on her own. Willingly. Eagerly. Sure, a dominant chord just sounded right, but she still wanted to know why. So we drew out a major scale and began to dive into the theory of WHY the dominant seven chord is spelled like it is, and why certain chords were major and certain ones were minor. All of this from a three-chord pop song, with no method or theory book.

For her homework, I gave her another song, and told her to write out the chords and practice playing them.

Fast-forward a few months: she maintained some classical repertoire in her studies, but retained it much better because she better understood the harmony behind the notes. She also whizzed through pop song after pop song, expanding into classic hits and even a few jazz standards. Her understanding of chords continued to develop, and she even became involved as the keyboardist for a small rock band comprised of students her age!

This approach works because the music comes first. Developing good technique is super important, and mastering technique and music theory takes time. However, if you don't have passion to keep driving you forward, you'll never stick around long enough to get the chance.

In future posts, I'll be digging deeper into the specifics of understanding chord symbols, and how to use them to get you closer to what you truly care about: the music you want to play.

Thanks for reading. And until next time, stay squirrelly.

Ben Lassiter lives in Durham, North Carolina, where he shares his rockstar talent with students from seven years old to adults. He has a master's degree in Jazz Studies from North Carolina Central University with an emphasis in Composition and Arranging. He also plays in the nationally renowned swing ensemble, The Mint Julep Jazz Band.

Check him out at his website, www.benjaminlassiter.com.